Shipping Prototypes at Hackathons

Learning how to share a vision with that inevitably awful first draft.

“Let’s give it up for ‘worse’!”

Tom Lehman of Rap Genius emceed this year’s HackMIT–a competition where teams try to pull off the most impressive stunt with technology in 24 hours.

The day before, he discussed the glory of poorly-written software, preaching that “worse is better” for hackathon projects. Teams only have a bit of time to build something amazing, so they better focus on the amazing bit, not ensuring there are elegant or proper solutions for all of the underlying coding problems for the project that judges and users will never see.

As expected, the crowd gave it up for “worse”. But when Lehman asked the crowd to “give it up for ‘better’,” people cheered for “better” just as loud as they did for “worse”.

Lehman wondered aloud whether anybody had learned anything in the past day.

Steve Jobs continually talked at Apple about how “real artists ship”, meaning that getting something out into the real world to inspire people about a vision was more important than getting a product out onto the market that fulfilled the maximum extent of the vision.

And as Fred Vogelstein discussed recently in NYT Magazine, Jobs applied this mentality to the iPhone project.

As early as 2003, a handful of Apple engineers had figured out how to put multitouch technology in a tablet.

The fundamental capabilities of the technology were amazing, but with the technology and resources available at Apple at the time, it was going to be impossible to launch a tablet in any sort of reasonable timescale.

They simplified the product somewhat, creating phone rather than a tablet. But buying a phone is complicated. It takes time for people to work out contracts with their carrier. They have to budget money. They need to tell their friends about how excited they are about the new product.

Apple needed to run a demo far before the product was ready.

Not only was he introducing a new kind of phone — something Apple had never made before — he was doing so with a prototype that barely worked. Even though the iPhone wouldn’t go on sale for another six months, he wanted the world to want one right then.

The difficulty was figuring out how to inspire the crowd without hitting any of the kinks that would shatter impressiveness of the vision. So, they constrained the scope of the demonstration to avoid those problems.

Hours of trial and error had helped the iPhone team develop what engineers called “the golden path,” a specific set of tasks, performed in a specific way and order, that made the phone look as if it worked.

And after the successful demo was over, they put an iPhone on display, but on a stand inside a transparent cylinder. People couldn’t touch and potentially find the problems with it. And, if anything, it visually elevated the iPhone from something normal to something special you might find in an art museum.

A year ago, I balked at the concept of going to a hackathon. They seemed like the clearest expression of the “brogrammer” concept, who skip sleep and binge guzzling Red Bull and beer while coding in an attempt to demonstrate how amazing they are.

And on a deeper level, I was frustrated with how British Airways and other organizations presented their hackathons as ways to “change the world” with concepts ready to present to UN delegates and other officials in a short period of time.

Initial hackathon concepts are just a start. They have to be prototyped and those prototypes need to be tested with users. A final concept to change the world–one that’s going to be worthwhile to present to lawmakers–is going to take persistence. It’s probably going change in response to new data about the world.

That’s why massive-growth startup accelerator Y Combinator has always been about finding smart people, and not obsessing over their current concept:

I care more about the founders than the idea, because most of the startups we fund will change their idea significantly. If a group of founders seemed impressive enough, I'd fund them with no idea. But a really good idea will also get our attention—not because of the idea per se, but because it's evidence the founders are smart.

Granted, hackathons like the Ungrounded are a great way to get pre-vetted groups of likely unconnected smart people to talk, enabling them to create amazing concepts down the road that they might not otherwise, but presenting the ideas developed at such an event to dignitaries always seemed like a bit of a stretch.

Over the summer, I decided to sign up for Greylock Hackfest with two friends and a friend of a friend I hadn’t met yet. The contest had a reputation for being a place where teams produced some pretty awesome bits of code.

During the opening speeches of the event, Julie Deroche and other members of Greylock Partners dealt with this issue head-on. Hackathons aren’t really the ideal place to find the next idea worth funding. But, they’re a way for Greylock to find new, interesting people and help interesting people find each other. Greylock can see how students get creative with product ideas and implementations when there are tightly limited resources–the core types of skills you’d need in an early-stage venture, in a startup or otherwise.

Basically, hackathons are a practice-run that Greylock can use to find who’s going to be able to pull off a demo like that very first iPhone presentation, rather than a way to actually find the next iPhone.

The crowd’s cheering for “better” during Lehman’s speech was probably mostly due to sleep deprivation at the time, but I’ve found a deeper underlying truth to the response.

After working at three major hackathons (Greylock Hackfest, HackNY, and HackMIT) and numerous other side projects (more on these in future posts), I’ve learned that getting started and getting something built that has laser-like focus on the bare minimum and doesn’t get lost in details is incredibly difficult. It’s something that I haven’t practiced sufficiently in my pet projects. And there isn’t a huge emphasis on it in school.

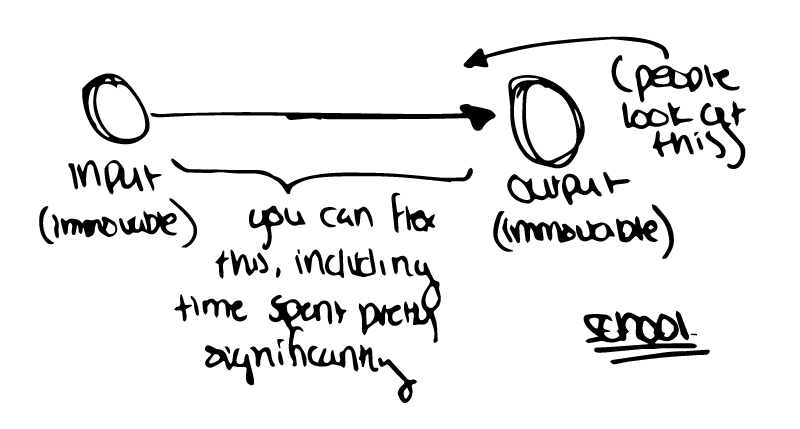

In a typical project for a university computer science course, you’re given a pretty tightly fixed input and told to give a pretty tightly fixed type of output. You have a fair amount of leeway to decide how much time to dump on building the problem. This is restricted by your other commitments as a student–but you probably have a week or two to get it done.

But more importantly, a project is graded on how “good” your implementation is according to various metrics about code quality, accuracy of transforming inputs to outputs, etc.

It’s a really fantastic system for teaching you the craft of computer science, which is foundational to building a software product. However, there’s skills beyond these–namely understanding how to pivot and how to understand what problem to solve in the first place–that are key to understanding how to launch a product that this model is not spectacular at conveying.

Hackathons are essentially the inverse of this model. The underlying goal of a hackathon is seeing how competitors figure out what vision is important to solve and what inputs and outputs to support that still demonstrate this vision.

Time is incredibly short in a hackathon. If a team tries to build an app that covered all of the real-world inputs and outputs for a vision, they won’t be able to be very ambitious with their vision. Or just fall flat and miss implementing the vision entirely.

The key to winning one is to figure out an incredible product vision and how to traverse a “golden path” like that of the iPhone demo to demonstrate that vision to the judges.

The judges–and for that matter, audiences seeing a demo of a first-generation product–will never see or care about the code used to accomplish that. It doesn’t even matter if you build something that’s not robust. You don’t have to give them the opportunity to touch the product.

Besides, writing something elegant, proper, and robust takes extra time that just doesn’t exist at a hackathon–much like the situations you’ll find in the early stages of a startup.

So, as Lehman says, here, worse is better.